I vape cannabis several times a day and have no intentions of stopping anytime soon. It’s never slowed my work ethic or turned me into a zombie. Instead, I feel more creative and at peace. I don’t have any life threatening health conditions or chronic pain, and I’ve never been one to take a lot of pharmaceuticals. However, since I’m not a “hippy” by any means, I tend to have a lot of non-cannabis-using friends who occasionally ask me about my frequent cannabis use. Invariably, the question that always comes up is, “…do you think that stuff rots your brain over time? I heard it makes people dumb if they use it too much…”

If you’re open about cannabis use, you’ll probably encounter this conversation at least once. Culturally, we’re used to the image of a stoner-burnout, a guy stuck in the 70’s that handles life like Jeff Bridges’ character in The Big Lebowski. We look at these people and we secretly wonder to ourselves, “did smoking cannabis all day every day make them this way? Will I be like that if I continue to use cannabis?”

When we talk about the safety of cannabis, we’re really talking about quite a few things. First, there are the things that we know as facts. Fact: It’s damn near impossible to overdose on cannabis. The amount of THC that would be needed to cause an overdose is such a large quantity that the volume alone makes it difficult to do. For instance, you could eat 100 of the strongest edibles—you’d probably be uncomfortably high for several days and spend most of that time sleeping, but you wouldn’t need to be taken to the hospital, and if you were, they’d tell you to go sleep it off. Then there’s the issue of immediate health consequences: also as fact, we have yet to see immediate harmful health consequences from cannabis. Although effects that can be classified as harmful (such as difficultly remembering, sensitivity to light, higher blood pressure, paranoia, etc.) are known to occur in some individuals when using cannabis, these effects disappear when the body has finished using up the involved cannabinoids. This is not the case with smoking tobacco or even common pharmaceuticals, which leave lasting changes within the body even after the chemicals involved have been metabolized.

However, the issues of toxicity and immediate consequences are entirely separate from the issue of long-term consequences. Unfortunately, getting a clear answer to whether there are long-term consequences is hard. Without following a really large group of people over their entire lifetimes and performing regular neuro-cognitive tests the whole way (good luck with that!), all we can do is compare groups of people who use cannabis and do not use and see if there are any differences in cognitive capacity of the two groups as a whole. This is, of course, prone to error because on an individual level, someone’s choice to use cannabis could be related to a pre-existing condition that already decreases neurological functioning. In a small study, even several patients can throw results. The results could also be population dependent and only observed in the local group chosen by the particular study. Thus, in order to reduce error, we really need to look at all studies that have ever been performed like this and combine their results together. That would give us the best answer as to the long-term effect of using cannabis.

Sounds great right? Not so easy as it turns out. Every study uses different tests for neurological function, with different scoring. Furthermore, the amount of “variability” differs with each study. Without getting into the math, variability is a measure of how spread-out the scores are. This matters, because for instance, if the observed difference between cannabis users and non-users scores is small compared to the average difference between all of the scores already, then the observed difference doesn’t mean as much and should not be weighted as heavily in the final computation. Whereas in a study where the observed difference between groups is large compared to the variability of scores, the observed difference is logically more significant. The difference in variability in each study makes it really difficult to just add the tests together into one numerical quantification of how cannabis affects neurological function. What ends up happening then is that most doctors/people just read a lot of the studies individually, come to a personal opinion, and then repeat that opinion on the nearest blog!

That’s why today we have a real treat for you:

A team from the University of California, San Diego decided to calculate “effect size” for each study, which in this case is the difference between average scores of cannabis vs. non-cannabis users, divided by the average standard deviation (a measure of variability). If you skimmed over that last sentence, don’t worry, it just means that the researchers expressed the difference in scores in a way that takes variability into account and allows the effect of using cannabis to be compared across multiple studies.

Afterwards, the researchers culled through various research databases, accumulating a list of 1,014 unique studies that attempted to find the effect of long-term cannabis use. However, not all of these studies were applicable. First and most obviously, an appropriate study must include a control of non-cannabis using participants for a comparison (which surprisingly, many studies do not). Secondly, valid neuropsychological tests must be used (not something random the research group made up). Third, the studies needed to take into account other potential substance abuse issues and psychiatric problems in the cannabis group. Fourth, the study needed to give the length of abstinence from cannabis in cannabis-users before testing. Many studies did not do this, and it’s a shame, because that means that in a lot of those cases they were actually testing participants that were still medicated or having residual effects from medicating prior. This would mean their results are not a measure of long-term changes but more a measure of the effects of being currently high on cannabis. Finally, the study needed to give enough information for the “effect size” to be calculated.

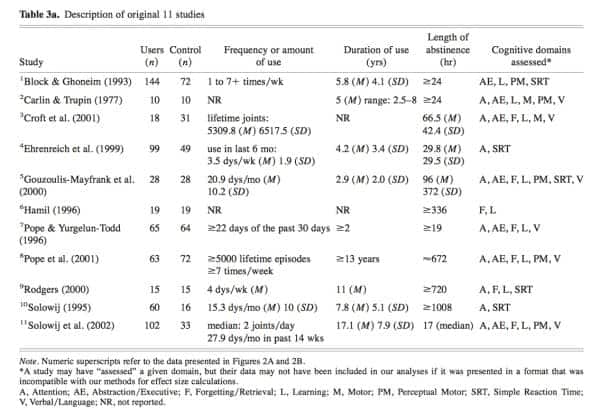

From these guidelines, researchers ultimately narrowed down 15 studies that fit the metric. These studies should receive particular attention and are included in the table below:

Inset: Table of studies that fit the guidelines set forth by Grant et. al

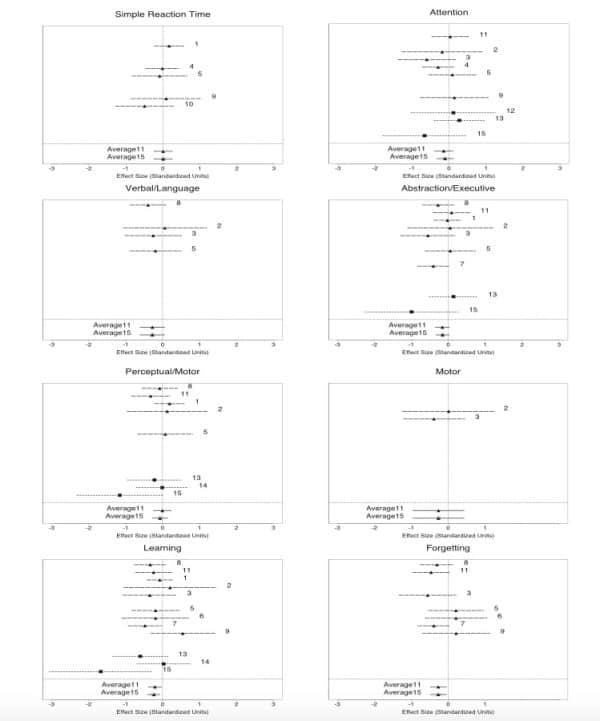

Since most studies included several experiments that tested different aspects of brain function, the studies were broken down into individual experiments which were then re-sorted together into the eight categories of simple reaction time, attention, abstraction/executive, verbal language, motor, perceptual, learning, and forgetting. From there, researchers averaged effect sizes in each category to get a total effect size for that aspect of neurological functioning.

The results are shown in the tables below:

Inset: Results of calculating effect size for all studies and combining them into specific groups based on neurological function.

What’s most important about these graphs is the number at the bottom of each that says “average15”, because that is the average effect size from all 15 studies’ data. As we can see, these averages are almost always just barely negative, suggesting there is some sort of negative neuro-cognitive effect. However, in almost all cases, the confidence interval for that average included zero. A confidence interval is an interval over which we can be 95% sure (or some other agreed amount sure) that the correct value is somewhere in between the two values listed. In other words, if zero is included between those two values, we cannot rule out that there was no effect at all! In fact, when all tests were added together, researchers calculated a 0.17% decrease in brain function. This is a small but noticeable difference test-wise. However, that difference becomes even smaller when you consider the incomplete removal of co-factors (for instance if people with different educational backgrounds are more likely to use or not use cannabis), the bias of cannabis users that were still slightly intoxicated during testing despite being cited as sober, and finally the fact that cannabis users in many of the studies were on average older than non-cannabis users and would therefore fare worse on neurological tests.

For those of you that skimmed to the bottom just to hear conclusions, the essential outcome is that numerically, from a mass consideration of reliable, accurate studies, we are not seeing a significant difference in long-term brain functioning. Backing this up, an additional study was recently conducted where long-term cannabis users were required to abstain from cannabis use for an entire month (Pope et. al). Researchers confirmed this abstinence in particpants by drug testing and ultimately found no observable difference between the cannabis-using group and the non-cannabis-using group at the end of the month. This suggests that any effects observed are in fact, residual from cannabinoids still being in the body as opposed to effects of the brain being structurally changed in an irreversible way.

Let me couch this by saying that just because a general long-term effect is not observed does not mean that specific areas of the brain are not being affected. After all, it’s very possible that the neurological tests selected by researchers did not access areas that were impacted. The most significant results seen were in the areas of learning and forgetting, so we’d like to see more research done in that region. However, by using multiple studies, we decrease the risk of bias and error, and we feel as confident as possible at this point in time that long-term cannabis use is safe.

Works Cited

Igor Grant, Raul Gonzalez, Catherine Carey, et. al. (2002) Non-acute (residual) neuro-cognitive effects of cannabis use: A meta-analytic study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (2003), 9, 679-689.

H.G. Pope, A.J. Gruber. (2001) Neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 909-915.