Endometriosis, although not frequently discussed by news media, affects more than 200,000 women in the US every year! During endometriosis, endometrial tissue, which usually grows inside the uterus, manages to transplant itself outside the uterus and continue growing. This growth can cause fibers of cells to form, making organs stick together, which results in severe pain. However, perhaps worse, the cells continue to behave as a healthy uterine lining would; they continue to swell, break down, and release blood along with the natural menstrual cycle. This activity can result in cysts forming, which leads to more pain, infertility, and eventually death. Sadly, while we have medicines that alleviate symptoms and decrease frequency of menstruation, we have nothing that eradicates the growths directly. In most severe cases, therefore, doctors are forced to operate to remove areas where endometrial tissue has bonded outside the uterus. Surgery, however, is always risky. Removing such growths comes with “significant morbidity”.

In past articles we’ve discussed how cannabinoids are being used to halt tumor growth in cell culture experiments and sometimes in actual rodent tumors. What essentially occurs is that cells with high growth profiles are encouraged to deactivate, leaving “healthy” cells alone. Although endometriosis does not involve cancerous growth, it does involve rapidly growing cells adhering outside of normal locations. As a result, researchers have postulated for some time that cannabinoids might also pose a treatment solution to endometriosis or at least be used to slow its development. One study from The American Journal of Pathology has tested this idea explicitly by investigating the effect of cannabinoid administration on endometrial cells (both in cell cultures and in growth implants in rodents).

While creating biological models of endometriosis in the lab is difficult, researchers are easily able to pull actual human tissue samples from women already undergoing surgery to remove endometriosis. During these surgeries, researchers are able to harvest tissue and transport that tissue to the lab within an hour of harvest, ensuring fresh, viable cells. In this case, researchers proceeded to split harvested tissue into two experiments. In the first experiment, tissues were broken apart and washed to result in individual cells. These cells were then suspended in cell-growing mediums and allowed to replicate and grow. Researchers wanted to ask: what is the effect of applying a cannabinoid receptor agonist to endometriotic cells? Readers will remember that cannabinoid receptor agonists are molecules like THC found in cannabis that activate human cannabinoid receptors. Rather than choose THC for this experiment, researchers chose a synthetic cannabinoid known as WIN 55,212-2 (WIN). WIN has been found to be a potent agonist and to have high therapeutic potential.

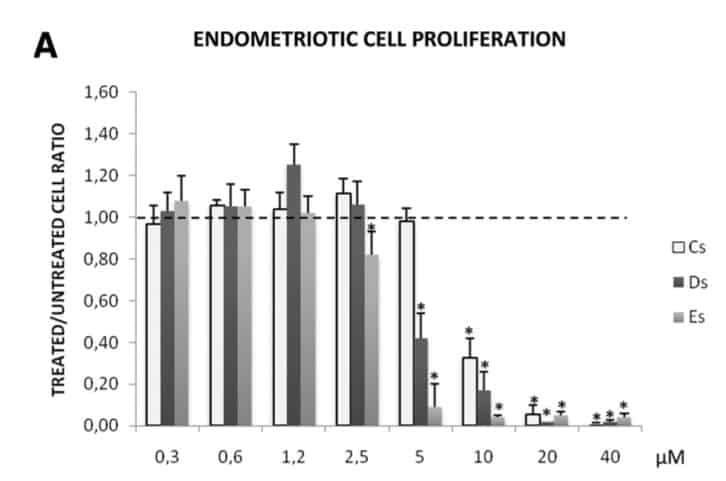

As seen below, the effect of adding WIN became clear at high doses. The graph below shows cell proliferation/growth (vertical column) plotted against WIN concentration added to the cells (horizontal row). Cs, Ds, and Es stand for the type of cell used, with Cs corresponding to inter-uterine “healthy cells”, Ds referring to cells taken from surface level growths, and Es referring to cells taken from deep cysts. Regardless of the cell type, readers can see that as the micromolar concentration of WIN (horizontal axis) increased past 5, cell proliferation plummeted! By 40, cell proliferation had all but stopped in all cell types, with between 96% and 99% reduction in all cases. Readers will notice the horizontal dotted line located at 1,00 on the vertical axis. This line represents the expected level of cell proliferation had no WIN been added, and in fact, this line matches the data at low concentrations of WIN. Breaking this all down, essentially what we’re seeing is a dose-dependent reaction to WIN, which means that effects increase with increased addition of WIN.

Researchers followed this test by confirming cell viability (essentially whether the cells were still alive) at various concentrations of WIN. In contrast to the proliferation study, cell viability was entirely unaffected by WIN at any concentration, indicating that while WIN may prevent cell counts from increasing, it is not particularly toxic to cells or likely to cause cell death. This is an important aspect for readers to note, because it would seem to indicate that cannabinoids might be used to halt the spread of endometriosis very effectively, however, from this experiment, they do not appear to be a replacement for surgery.

Of course, petri dishes are like Vegas (what happens there stays there!). While petri dishes are cheap, simplified ways of testing general reactions, results may be either more or less effective when tested in more realistic biological settings. As a result, researchers sought to test WIN in actual rodent models. Again, while finding naturally occurring endometriosis in rodents of the same general age, size, and weight might be impractical, researchers were able to create an effective model by implanting human endometriotic tissue. Researchers cut open rodents and stitched harvested human tissue onto vital organs before allowing the rodents to heal. They then measured the volume of the tissue implants on the first day, as well as three weeks later. Half of the rodents received no treatment to serve as a control group, while the other half began to receive injections of WIN five days a week for the second and third weeks of recovery. In the end, by comparing growth volume, researchers were able to understand if the growths grew, shrunk, or remained unaffected. Again, the results seemed to indicate a very strong potential for WIN as pharmacological target for endometriosis treatment. While growth volumes remained unchanged in the “no treatment” group, growths in the treatment group shrunk by 41% compared to the original volume. In contrast to the experiment above, this would seem to indicate that WIN injections are actually capable of reversing endometriotic growths rather than just halting the spread. Were this experiment to be replicated in humans successfully, WIN might very well represent an immediately viable treatment option for endometriosis.

As always, however, human testing is a long way off. At this point in time, it is impossible to know what treatments, if any, will stem from cannabinoids. However, based on these experiments, we have very good reason to believe that cannabinoids will prove useful in future endometriosis treatment. Aside from the ability to halt endometriotic cell proliferation, cannabinoid agonists have been shown to reduce chronic pain, which helps tackle one of the main symptoms of endometriosis itself. Moreover, cannabinoids have been shown in some experiments to halt fibrosis, meaning they might help prevent organs from sticking together as a result of endometriosis. In short, the entire suite of effects produced by cannabinoids seems to go hand in hand with endometriosis treatment. Women suffering from endometriosis may therefore be interested in supplementing traditional medical treatment with topical cannabis rubs rich in cannabinoid receptor agonists.

Works Cited

Leconte M, Nicco C, Ngô C, et al. Antiproliferative Effects of Cannabinoid Agonists on Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis. The American Journal of Pathology. 2010;177(6):2963-2970. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2010.100375.