Chronic neuropathic pain affects between 1% and 2% of all adults, which means that you’ve likely encountered someone suffering from neuropathic pain or experienced it directly. As would be expected from the sheer prevalence, there are many causes for such pain, ranging from illness, such as diabetes, to specific events of trauma, such as car accidents or work injuries. Traditionally, neuropathic pain has been considered “refractory” to treatment options, meaning that it is difficult to manage consistently and effectively. However, new research has pointed to cannabis as a viable option for treatment of neuropathic pain.

As has been the basis of many of the therapeutic effects of cannabis, the anti-inflammatory properties of cannabis are likely responsible for the observation of cannabis use reducing neuropathic pain. Although the specific mechanisms of neuropathy are poorly understood, it is speculated that glial cells, which are the immune system enforcers of the brain and spinal cord, are not functioning properly or are overcompensating for injury by over-producing inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-1beta. It is also known that the endocannabinoid system is capable of regulating and signaling production of this very molecule, as well as other inflammatory molecules, which draws an obvious link between cannabis consumption and neuropathy.

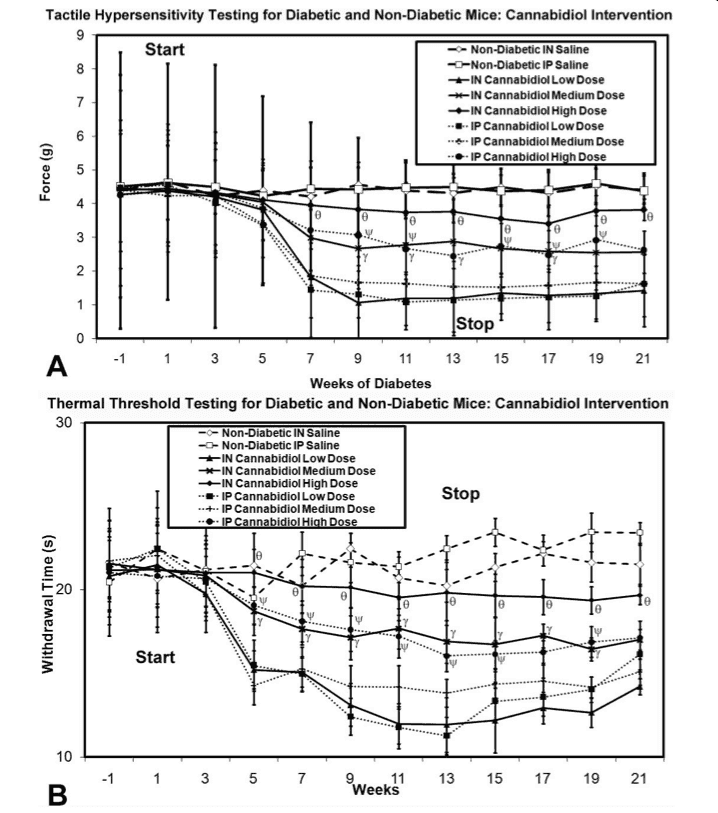

However, while the specific mechanism of action is not mapped, researchers are continuing with the testing of cannabinoids in models of neuropathy. One particularly comprehensive study from the University of Calgary focused on neuropathy stemming from diabetes, which is a common side effect of the illness (50% of diabetes patients suffer neuropathic pain). In this study, researchers used rodents with artificially induced diabetes and subsequent neuropathy. Once diabetes was confirmed, researchers then tested application of both cannabinoid receptor agonists (drugs which activate cannabinoid receptors) as well as cannabinoid receptor antagonists (which block receptor activation) and then ran various tests on the rodents to evaluate pain. Two common indicators of neuropathic pain are pain due to stimulus that would not normally produce pain as well as over-sensitivity to temperature, both experienced by diabetes patients. To quantify these experiences for the rodents, researchers used both a metal rod prodding test (that measured the force necessary for the rod to cause discomfort and force the rodent to move) as well as a thermal test which heated the rodents paws and recorded exposure time necessary to cause the rodent to move its paws. Rodents suffering from pain will consistently react more quickly than those un-pained by the prod or heat being applied.

The results to this study showed great promise; both major types of cannabinoid receptor agonists were shown to ameliorate hypersensitivity to mechanical or thermal stimulus. As seen in the accompanying graphs, higher doses of cannabinoid receptor agonists also corresponded to increased effectiveness in muting pain when administered both nasally and intravenously.

Regardless of how these agonists enter the body of the rodent, they are effective at reducing pain commonly associated with neuropathy and specifically neuropathy resulting from diabetes. As it turned out, receptor antagonists seemed to have no effect at all in any trial, further implicating that activation of these specific cannabinoid receptors is responsible for the changes in pain threshold observed. However, not content to stop at this stage, researchers also performed surgical dissections to analyze the accumulation of microglia in the spinal cord and in the thalamic part of the brain. Upon doing this, the study found that cannabidiol (CBD) was capable of reducing the accumulation of microglia in these areas, even after administration had ceased.

As it turns out, a study from the University of Milano-Bicocca performed a similar experiment two years prior, with many of the same design considerations. Although this study was much less broad and objective, the results mirror those observed from the Calgary group, with additional focus given to the effect of CBD on Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), since many of the neurons that transmit pain are supported by NGF. Not surprisingly, patients with diabetes are known to have consistently lower levels. In this study, researchers found that NGF content in rodents was restored to normal following repeated treatment with CBD, which indicates that cannabis use may go beyond attenuation of symptoms but further into actual prevention and restoration of nerve damage via contributing to new nerve growth.

The largest looming question of any rodent based research, of course, is whether the results found in the lab will be duplicated in the field of human treatment, which differs substantially, biologically, externally, and socially. In other words: beyond mouse trials, how effective are cannabinoids at reducing pain in actual human cases of neuropathic pain? One Canadian research group at McGill University set out to answer this question. For the design of the study, the group screened 116 patients suffering from neuropathy, ultimately selecting 23 that had not used cannabis within the previous year and therefore would more accurately reflect how a non-active-consumer might benefit from the start of cannabis therapy. The ultimate goal of the study was to test how various levels of THC administered affect assessments of pain, sleep, and mood states, both during use and in the period following use.

After supervision during an initial session, patients were given a schedule to follow for consuming their cannabis specimens, with the instructions to re-dose three times a day for a five day period, followed by a nine day “wash out” period, designed to allow to the THC to leave their systems while observing continued effects of the THC administration. As it turned out, “no evidence of significant carryover” existed for any outcome, meaning that in this study, pain relief was limited to time during exposure to cannabis. However, the study did confirm with statistical significance that the average daily pain intensity was lower consistently by a full step on a 10-step pain ladder and that mood and sleep were also improved.

While this might be expected, two interesting points emerged from the study. One stumbling block to any type of research involving THC and pain or mood assessment has been that it is difficult to control for the effects of placebo, or in other words, to account for effects not produced from the actual substance, but produced from the patients’ perceptions of how the substance will affect their pain or moods. In most studies, patients are given sugar pills so that they will not know whether what they are consuming is the drug or not, eliminating their reporting bias. However, with THC, most patients know immediately if they have been dosed, due to the psychoactive effects that manifest. To get around this, the group created a range of cannabis samples with THC levels from 0% to 9%, and ran tests to see if the patients could properly identify in what order they had been dosed or if they had been dosed at all. Due to both the relatively low doses of THC, which were on the threshold of perception, as well as the similarity in taste even with the 0% THC cannabis, patients were not able to identify dosing, which illustrates the effectiveness of this approach and the ability to have true placebo cannabis testing in humans.

Another interesting point is that the study focused on THC, excluding and ignoring the effects of cannabidiol (CBD), which must have been present as well in the cannabis samples used. It is very possible that the increased THC cannabis samples also had increased CBD levels or other cannabinoid levels, meaning that to attribute the effects here to THC is hasty and the study can only objectively be observed as the effectiveness of cannabis as a whole (including all cannabinoids, terpenoids, and other chemicals), as opposed to the effectiveness of THC in treating neuropathic pain.

However, the bottom line is that evidence is supporting both rodent models and human models of treatment of neuropathic pain with cannabis. It is reasonable to believe that these effects will continue to be honed in on and re-produced with more direct chemical analogues, and that in the meantime, patients suffering from neuropathic pain may find comfort in cannabis use.

Works Cited

Mark A. Ware, Tongtong Wang, Stan Shapiro, Ann Robinson, et al. (2010) Smoked cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: a randomized controlled trial, Canadian Medical Association Journal (2010) 182 (14).

Cory Toth, Nicole Jedrzejewski, Connie Ellis, and William Frey. (2010) Cannabinoid-mediated modulation of neuropathic pain and microglial accumulation in a model of murine type 1 diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, Molecular Pain 2010 6:16

Francesca Comelli, Isabella Bettoni, Maripia Colleoni, et al. (2008) Beneficial effects of a Cannabis sativa extract treatment on diabetes-induced neuropathy and oxidative stress, Phytotherapy Research Journal (2009) 23:12