As the U.S. continues the process of legalizing medicinal cannabis use, state by state, one of the biggest concerns from opponents remains the impact on adolescents. Although teenagers are not actually permitted to consume cannabis in most states, it’s logical enough that easier access and less cultural stigmatization of cannabis may increase rates of adolescent consumption. Factually, we haven’t seen definitive research either way on how cannabis affects adolescents, and lifetime cannabis users statistically have no cognitive impairment. However, as a society, it’s our responsibility to approach the issue carefully, for two reasons. First, as researchers often point out, the teenage brain is not fully formed, and medicines that may be safe for adults may not be safe for youth. The idea is that at the time regulatory patterns are being formed, cannabis use could theoretically alter the baseline balance permanently. Secondly, even a decreased cognitive performance during a temporary time period could hurt adolescents’ chances at higher education, which could be equally devastating.

In other words, this topic deserves immediate attention from the scientific community. However, one familiar roadblock stands in the way; it’s difficult to control for conflated variables. Especially in the case of adolescents, those that currently choose to consume cannabis illegally are much more likely to exhibit high-risk behaviors that affect cognitive development (such as other drug use) or to already struggle in school. Performing a simple statistical regression may therefore falsely give the appearance of causation stemming from cannabis use. Thus, true understanding of the connection (or lack of connection) must inevitably account for other sociological, economic, and performance variables.

As a result, cohort studies are some of our biggest allies in answering this type of question. A cohort study is a study that follows a group of people with common characteristics over time, rather than a lot of different types of people at one moment in time. This allows researchers to compare both pre and post cannabis use, as well as to eliminate some of the observed effects that actually stem from comparing different groups of people. A new study released by the University College of London has made use of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a cohort study that has followed women and their children since pregnancy, to try to examine the effect of cannabis use on adolescents. In this case, the cohort consists of children born in 1992 in Avon County, England. Although the cohort includes nearly 15,000 pregnancies, only 2,235 individuals had sufficient data for inclusion in this cannabis study. Cannabis use data was pulled from self-reported answers at age 15, with categories of “never”, “less than five times”, “five to 19 times”, “20-49 times”, “50-99 times”, and “100 times or more”. A fake drug question was used midway through the questionnaire to weed out individuals speeding through the assessment. One obvious drawback to this approach is that teenagers fearing repercussion might underreport cannabis use. As a result, answers were made confidential to elicit the most honest responses. Additionally, participants were administered the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (3rd Edition) at both ages 8 and 15, giving a record of pre and post cannabis use IQ.

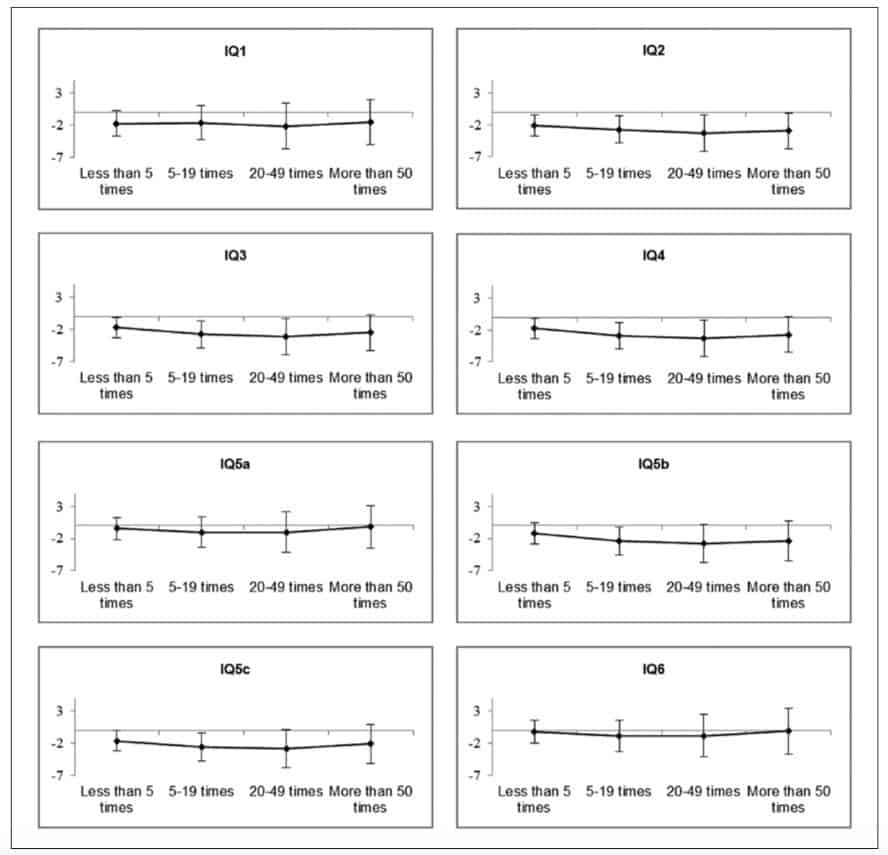

In the end, 23.5% reported using cannabis at least once, confirming the high potential of cannabis exposure and therefore the significance of this study. Below we can see the raw data, in terms of the calculated effect of cannabis use on IQ. The average effect on IQ is plotted for each category of user. Data points that exist furthest from the horizontal line represent the greatest negative effect on IQ, while data points that exist on the line itself show no effect (since the line is drawn at 0). As readers can see, eight different versions of the plot have been provided here, which each one accounting for a different set of co-factors that may contribute to cognitive decline.

As we can see, most of the models appear to show a negative correlation between cannabis use and IQ. For instance, Model IQ3, which only accounted for maternal, early-life, and childhood behavioral factors, showed essentially the same negative effect the unadjusted data in IQ1 showed.

However, take a look at IQ5A, which controlled for cigarette use. Notice how greatly reduced the effect is here. In fact, in this plot, heavy users of cannabis (those that used more than 50 times) showed almost no effect at all. This implies that the observed effect had a strong association with cigarette use, as opposed to cannabis. Why that would occur is not immediately clear. While numerous other studies have found a similar correlation between cigarette use and decreased IQ, biological lab tests with nicotine have not shown this type of effect on neurons. That observation hints that cigarette use could be some sort of blanket marker for other behavior or that other chemicals in cigarettes are contributing to cognitive decline.

Regardless, when all cofactors are finally controlled for in graph IQ6 (cigarette use, alcohol use, behavior and mental health factors, and maternal factors), the effect disappears entirely. In other words, when appropriate cofactors are controlled for, there appears to be no link between reduced IQ and adolescent cannabis use.

This conclusion should not be confused with the question of whether cannabis use is safe for adolescents. Any type of psychoactive stimulation in adolescents, whether from cannabis or another substance, may contribute to decreased inhibition, exacerbation of mental illness, and other effects that may have little to do with cognitive performance. The question of whether a substance is appropriate for an individual goes well beyond cold, scientific observations, and at this point in time, most credible physicians do not support adolescent use except in extreme health situations, such as epilepsy.

Instead, what this study illustrates is that the assumed link between cannabis use and adolescent IQ is flawed. Reports of associations should be retroactively examined to account for relevant cofactors, or else the data from those reports will be misleading and unconstructive to the greater societal conversation about cannabis use.

Works Cited

C Mokrysz, R Landy, SH Gage, MR Munafo, et al. “Are IQ and educational outcomes in teenagers related to their cannabis use? A prspective cohort study.” Journal of Psychopharmacology (2016) 1-10. DOI: 10.1177/0269881115622241.